Phil’s Findings #9: Wood

18 July 2011

We humans have quite a strange relationship with wood. On the one hand, we use it as a strong and durable construction material, and indeed it has been heavily relied on ever since the earliest of civilisations tried their hands at construction. On the other hand, wood is used as a disposable fuel source, unleashing the energy which it captures from the sun during its growth. The result is that we see wood as simultaneously being something that can be strong and long lasting, and short lived and disposable.

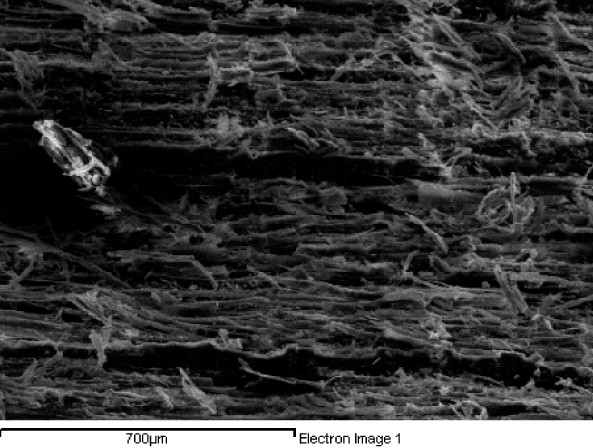

The strength of wood comes from its structure at a very small scale. The fundamental difference between animal cells and plant cells is that plant cells have stronger walls. Animal cells are not rigid structures, which means us animals require some sort of skeleton or rigid structure to support our bodies. Plants do not have skeletons, and their strength is instead drawn from the rigidity of individual cells and how they build up to create the entire plant structure. In wood, these cells are long tubular structures with walls composed of strands of a polymer called cellulose, a type of carbohydrate. These strands are stuck together in ordered rows by a sort of molecular glue called lignin, and it is this arrangement that ultimately gives wood its strength. The tubular wood cells are lined up and stuck together vertically all along the tree trunk, giving wood its fibrous texture. The picture below is an electron microscope image I took of the surface of some basswood, and you can see the individual fibres ripped up from the surface where the wood has been cut.

When you touch the surface of wood it tends to feels warm, but when you touch a metal or stone surface they tend to feel cold. But the things around us locally in our environment, like your desk for example, are all at the same temperature. So why does the wood feel warmer? Well, our perception of temperature through touch is really based on changes of temperature, not absolute temperature. When you touch metal or stone, it draws heat from your fingers quickly, and therefore feels cold. However, when you touch wood, it draws heat from your fingers very slowly, and therefore feels warm. This is because wood has low thermal conductivity, a property which makes it very good for making insulating materials like pan handles or wooden spoons where metal ones would burn you. The molecules and cells in wood, and the way they are packed in the structure, do not vibrate and bang together enough to transfer heat in the same way that metal or stone does. Also, wood has a lot of air trapped inside, which scuppers the attempts of heat to penetrate through the structure. The result is that, when you touch the surface of wood, the heat from your finger finds it hard to jump over into the wood, and thus you do not sense a quick temperature change.